The Rise and Rise of Bacteriophages References

Bacteriophage therapy, the use of bacteriophages to treat infection, was used extensively in the former Soviet Union throughout the twentieth century, not least because the antibiotics that were adopted widely across the western world were difficult to access in the Russian States. Nevertheless, phage therapy enjoyed a moment of Hollywood glamour in 1961 when newspapers reported that film star Elizabeth Taylor was treated for pneumonia using a staphylococcus bacteriophage lysate1.

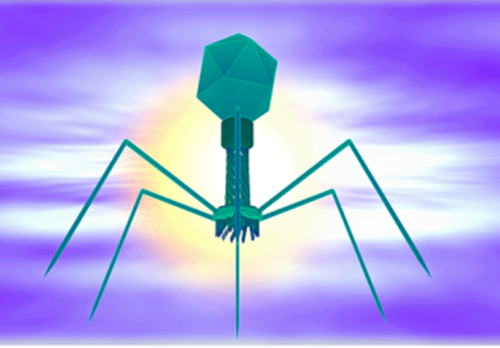

Bacteriophages, or phages for short, are viruses that specifically infect bacteria. Composed of nucleic acid within a protein structure, phages force their host bacteria to produce viral rather than bacterial components. New phages assemble within the bacterial cells and those that rupture the host are known as lytic phages. The observable effect of lytic phages was first reported in 1896 by a British bacteriologist, Ernest Hankin, who found that an agent which lysed Vibrio cholerae could pass through bacterial filters2.

French scientist, Felix d’Herelle, is credited with being the first to develop phage therapy and achieved success in 1919 when he stopped a typhoid outbreak in chickens using a phage isolated from a faecal sample of a typhoid-infected chicken. He also trialled phage therapy in humans, treating a child with dysentery with a phage isolated from another patient with dysentery, having first tested it on himself.

There has been a general public aversion in the western world to the concept of using viruses to treat bacterial infections, but the growing crisis of antimicrobial resistance means there are increasing medical and economic reasons to reconsider phages. Numerous research groups are re-evaluating the clinical use of phages and more than ever are considering their value for wider applications. Recent examples include the use of phages to reduce the level of salmonella in swine slurry3, the inactivation of Listeria monocytogenes on a cured dried meat product4, and the impact of phages on biofilms5.

Phages are still commonly used as epidemiological tools to investigate outbreaks of infection. By the1960’s many public health and hospital laboratories in the United Kingdom had adopted phage typing for the characterisation of coagulase positive staphylococci6. Routine phage typing methods for Salmonella, Shigella and other genera quickly followed. However phage-typing techniques in reference and specialist microbiology are slowly being superseded by whole genome sequencing technologies7.

The National Collection of Type Cultures holds a range of phages that are not currently available to the wider research community. However, a new project starting in May 2018 will focus on rebanking and updating this collection and we look forward to making the phages readily available in due course.

References

- https://psmag.com/nature-and-technology/elizabeth-taylor-great-grandpa-future-antibiotics-84626

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2555522/pdf/bullwho00326-0092.pdf

- https://norkinvirology.wordpress.com/2015/05/20/felix-dherelle-the-discovery-of-bacteriophages-and-phage-therapy/

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0929139316302785?via%3Dihub

- http://www.mdpi.com/2076-2607/4/1/4/htm

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5244418/pdf/srep40965.pdf

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5727591/